Conveyor Belt Tracking / Training

Tracking/Training the Belt Procedures

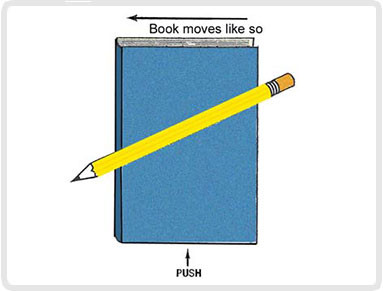

Training or tracking the belt on your radial stacker or conveyor system is a process of adjusting idlers, pulleys and loading conditions in a manner which will correct any tendency of the belt to run other than centrally. The basic rule which must be kept in mind when tracking a conveyor belt is simple, "THE BELT MOVES TOWARD THAT END OF THE ROLL/IDLER IT CONTACTS FIRST." You can demonstrate this for yourself by laying a small dowel rod or a round pencil on a flat surface in a skewed orientation. Then lay a book across the dowel rod and gently push push/roll it in a line directly away from you. The book will tend to shift to the left or right depending upon which end of that dowel rod the moving book contacts first.

When all portions of a belt run off through a part of the conveyor length, the cause is probably in the alignment or leveling of the radial stacker or conveyor structures, idlers or pulleys in that area.

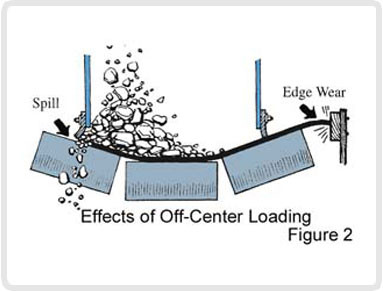

If one or more portions of the belt run off at all points along the conveyor, the cause is more likely in the belt itself, in the splices or in the loading of the belt. When the belt is loaded off-center, the center of gravity of the load tends to find the center of the troughing idlers, thus leading the belt off on its lightly loaded edge. (Figure 2)

These are the basic rules for diagnosis of belt running troubles. Combinations of these things sometimes produce cases that do not appear clear-cut as to cause, but if a sufficient number of belt revolutions are observed, the running pattern will become clear and the cause disclosed. The usual cases when a pattern does not emerge are those of erratic running, which may be found on an unloaded belt that does not trough well or a loaded belt which is not receiving its load uniformly centered.

Factors Affecting the Training of a Conveyor Belt

Reels Pulleys and Snubs

Relatively little steering effect is obtained from the crown of conveyor pulleys. Crown is most effective when there is a long unsupported span of belting, (approximately four times belt width) approaching the pulley. As this is not possible on the conveyor carrying side, head pulley crowning is relatively ineffective and is not worth the lateral mal-distribution of tension it produces in the belt.

Tail pulleys may have such an unsupported span of belt approaching them and crowning may help except when they are at points of high belt tension. The greatest advantage here is that the crown, to some degree, assists in centering the belt as it passes beneath the loading point, which is necessary for good loading. Take-up pulleys are sometimes crowned to take care of any slight misalignment which occurs in the take-up carriage as it shifts position.

All pulleys should be level with their axis at 90° to the intended path of the belt. They should be kept that way and not shifted as a means of training, with the exception that snub pulleys may have their axis shifted when other means of training have provided insufficient correction. Pulleys with their axes at other than 90° to the belt path will lead the belt in the direction of the edge of the belt which first contacts the misaligned pulley. When pulleys are not level, the belt tends to run to the low side. This is contrary to the old "rule of thumb" statement that a belt runs to the "high" side of the pulley. When combinations of these two occur, the one having the stronger influence will become evident in the belt performance.

Carrying Idler

Training the belt with the troughing idlers is accomplished in two ways. Shifting the idler axis with respect to the path of the belt, commonly known as "knocking idlers," is effective where the entire belt runs to one side along some portion of the conveyor or radial stacker. The belt can be centered by "knocking" ahead (in the direction of belt travel) the end of the idler to which the belt runs. Shifting idlers in this way should be spread over some length of the conveyor, or radial stacker, preceding the region of the trouble. It will be recognized that a belt might be made to run straight with half the idlers "knocked” one way and half the other, but this would be at the expense of increased rolling friction between belt and idlers. For this reason all idlers should initially be squared with the path of the belt and only the minimum shifting of idlers used as a training means. If the belt is over-corrected by shifting idlers, it should be restored by moving back the same idlers, not by shifting additional idlers in the other direction.

Obviously such idler shifting is effective for only one direction of belt travel. If the belt is reversed, a shifted idler, corrective in one direction, will misdirect in the other. Hence reversing belts should have all idlers squared up and left that way. Any correction required can be provided with self-aligning idlers designed for reversing operation. Not all self-aligners are of this type, as some work in one direction only.

Tilting the troughing idler forward (not over 2°) in the direction of belt travel produces a self-aligning effect. The idlers may be tilted in this manner by shimming the rear leg of the idler stand. Here again this method is not satisfactory where belts may be reversing, as illustrated in Figure 3.

This method has an advantage over "knocking idlers" in that it will correct for movement of the belt to either side of the idler, hence it is useful for training erratic belts. It has the disadvantage of encouraging accelerated pulley cover wear due to increased friction on the troughing rolls. It should therefore be used as sparingly as possible - especially on the higher angle troughing idlers.

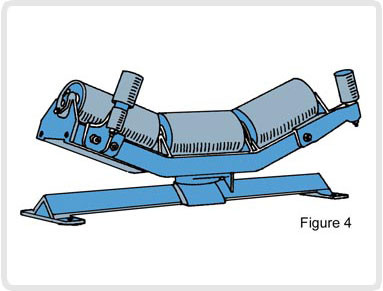

Special, self-aligning troughing idlers like the one to the right are available to assist in training the belt. (Figure 4)

Return Idlers

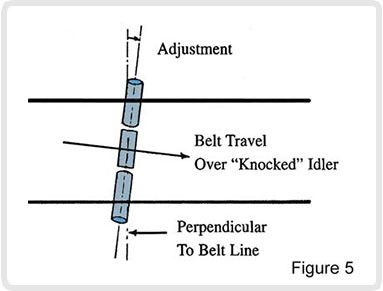

Return idlers, being flat, provide no self-aligning influence as in the case of tilted troughing idlers. However, by shifting their axis (knocking) with respect to the path of the belt, the return roll can be used to provide a constant corrective effect in one direction. As in the case of troughing rolls, the end of the roll toward which the belt is shifting should be moved longitudinally in the direction of return belt travel to provide correction. (Figure 5)

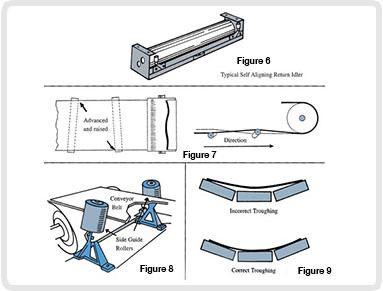

Self-aligning return rolls should also be used. These are pivoted about a central pin. Pivoting of the roll about this pin results from an off-center belt and the idler roll axis becomes shifted with respect to the path of the belt in a self-correcting action. (Figure 6) Some return idlers are made with two rolls forming a 10° to 20° V-trough, which is effective in helping to train the return run.

A further aid to centering the belt as it approaches the tail pulley may be had by slightly advancing and raising the alternate ends of the return rolls nearest the tail pulley. (Figure 7)

Assuring Effectiveness of Training Rolls

Normally, extra pressure is desired on self-aligning idlersand, in some cases, on standard idlers where strong training influence is required. One way to accomplish this is to raise such idlers above the line of adjacent idlers. Idlers or bend pulleys on convex (hump) curves along the return side have extra pressure due to component of the belt tension and are therefore effective training locations. Carrying side self aligners should not be located on a convex curve since their elevated positions can promote idler juncture failure of the carcass.

Side Guide Rollers

Guides of this type are not recommended for use in making belts run straight. (Figure 8) They may be used to assist in training the belt initially to prevent it from running off the pulleys and damaging itself against the structure of the conveyor system. They may also be used to afford the same sort of protection to the belt as an emergency measure, provided that they do not touch the belt edge when it is running normally. If they bear on the belt continually, even though free to roll, they tend to wear off the belt edge and eventually cause ply separation along the edge. Side guide rollers should not be located so as to bear against the belt edge once the belt is actually on the pulley. At this point no edge pressure can move the belt laterally.

The Belt Itself

A belt having extreme lateral stiffness, relative to its width, will be more difficult to train due to its lack of contact with the center roll of the carrying idler. Recognition of this fact enables the user to take extra precaution and, if necessary, load the belt during training to improve its steer ability. Observation of troughability design limitations will normally avoid this trouble. (Figure 9)

Some new belts may tend to run off to one side, in a certain portion or portions of their length, because of temporary lateral mal-distributions of tension. Operation of the belt under tension corrects this condition in practically all cases. Use of self-aligning idlers will aid in making the correction.